|

The clinical anatomy of the

respiratory tract starts at the external nares or nose. The pig has a large horn plate, perforated

by the two nares. This rostal plane or

rostrum is used as a rooting and exploration organ and combined with the neck

muscles is extremely strong. It is

not unusual to have areas of bruising or erosion to the dorsal tip of the

rostal plane. The nose is secondarily

supported by a bone in the nose the rostal bone. There are few or no hairs on the external surface of the nares.

|

|

|

|

|

Detail

of rostal plane with the external nares

|

Cross-section

of the nose at the level between premolar 1 and premolar 2.

|

|

Interior to the nares is the

nasal cavity which is largely filled by the nasal turbinates. The nasal cavity is divided into two

sections by a cartilage septum the nasal septum, which is normally straight. In each of the two nasal chambers there

are two outgrowths, on from the dorsal wall as a pundulous outgrowth the

dorsal turbinate and on the lateral wall of the nasal chamber and complex

biscrolled structure the ventral turbinate.

If the nasal chamber is sectioned in a transverse plane between premolar

1 and premolar 2 the ventral turbinates effectively fill the entire nasal

chamber in the normal pig. The

position of the premolar 1 and premolar 2 is indicated by the lateral

commissure of the mouth.

The back of the upper

respiratory tract is the tonsils which act as a major lymph node sampling

both food and materials brought from the nasal chamber and the

trachea/bronchi. The surface of the

turbinates are covered in a mucocilary escalator which moves from the nares

to the tonsils and oesophagus where the mucus is swallowed and the material

killed by the acidic environment.

|

|

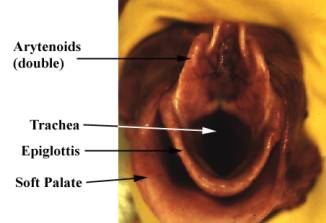

The middle respiratory tract is

defined by the larynx which lies at the root of the tongue. The pig has a large epiglottis which during

eating completely protects the entrance of the trachea allowing the pig to

eat and breath at the same time.

|

|

|

|

|

Root of the tongue and larynx

|

The entrance to the larynx (hand held)

|

|

Ventral to the large epiglottis

is a paraepiglottis fold, which can be troublesome when intubating a

pig. Intubation is difficult because

the larynx can be difficult to visualize as the pig does not have a wide

gape. During intubation the tube may

miss the larynx and enter the paraepiglottis fold, confusing the clinician

into thinking intubation has been successful. Note that in the pig the arytenoids are double.

|

|

|

|

The general layout of the chest with the ventral

surface removed.

|

|

|

At postmortem the respiratory tract

should be removed by making an incision along the medial border of the

mandible cutting through the hyoid apparatus and releasing the tongue. Pull

the tongue caudally and dissect the larynx and through the chest inlet. The lungs should easily strip away from

the pleura.

The incision

should be continued through the diaphragm ultimately to the rectum.

The photograph left

demonstrates the pluck without the liver and intestines attached.

|

|

The trachea starts below the

larynx. The trachea is supported by

incomplete cartilaginous rings. This

assists the clinician as once the larynx is incised the incision can easily

be continued right to the bottom of the right and left major bronchi to the

bottom of the lung.

|

|

|

|

|

Detail

of tracheal rings

|

Detail

of right tracheal bronchus

|

|

The trachea has three major

bronchi, a small right tracheal bronchus which feeds the right apical lobe and

the two major bronchi each which feed the rest of the lung. Clinically the right apical lobe is

important as this part of the lung is nearest the tonsils and is most

susceptible to descending pathogens for example it is often the most

consolidated area in cases of enzootic pneumonia.

|

|

|

|

Detail

of end of bronchi cut surface at the caudal position in the lung.

|

|

|

The turbinates, trachea and bronchi are lined by a cells

covered in cilia. On the surface of the

cilia is a mucus layer. This layer,

captures in falling particles between 3 and 1.6 mm in size. These particles are then moved by the

cilia caudally from the nose to the throat or cranially from the lower

bronchi to the throat. The

mucociliary escalator is a major component of the defense of the respiratory

tract.

|

|

|

|

Lungs

dorsal view

|

|

|

|

Lung

ventral view

|

|

The lung can be easily divided

into seven distinct lobes right and left apical, cardiac and diaphragmatic together

with the accessory lobe (visible on the dorsal view). During a clinical examination each of

these lobes should be examined in detail.

The surface of each lobe should be examined for pleurisy. Note the right apical lobe, as described

previously. The lung may require to

be further dissected to reduce its bulk to allow adequate palpation. The bronchial lymph nodes (of which there

are several) should be noted in the mediastinum on the ventral surface after

manual partition of each lung.

|

|

Once the lung is examined in detail, examine the

heart. If there is no gross evidence

of any blood vessel abnormalities, such as a patent ductus, remove the heart

from the respiratory pluck.

Peal away the pericardial sac and examined for

pericarditis. Open the heart using

four incisions:

- Incise into the right

auricle and continue the incision into the right venticle cutting

through the right AV valve. Keep

the incision close to the interventiculum septum.

- Incise into the left

auricle and continue the incision into the left venticle cutting through

the right AV valve. Keep the

incision close to the interventiculum septum.

- Using the point of

the scissors, find and cut into the aorta from the left ventricle

- Turn the heart over, find

and cut into the pulmonary artery from the right ventricle.

The heart can now be examined in detail noting the

pericardial wall, the right and left AV valves, noting any abnormality of the

interventricular septum and finally the pulmonary and aortic valves.

|

|

|

|

|

Parietal surface of the heart dorsal view

|

Parietal surface of the heart ventral view

|

|

|

|

Heart opened, right side.

|

|

|

|

Heart opened, left side

|

|

The pleura covers both the surface of the lung and the inner

wall of the chest. It should be

examined in detail for signs of pleurisy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|